Thesis: Comparing UAV and Pole Photogrammetry for Monitoring Beach Erosion

Written on September 29th, 2021 by Jack Gonzales

On August 25th, 2021, I successfully defended my thesis titled: Comparing UAV and Pole Photogrammetry for Monitoring Beach Erosion. As of September 14th, the Virginia Tech Graduate School officially approved my final thesis document, thus fulfilling all requirements for my MS in Geography. You can read the entire document here, or look below for the gist of my thesis project.

Introduction

Structure from Motion (SfM) photogrammetry has been widely used for geomophology research and surveying in aborad range of environments. SfM uses a series of overlapping images from a any digital camera to identify matching points in sequential images and construct a 3D model of a subject. For topographic applications, a high aerial perspective is desired, such as that from an aircraft or tall platform. Between advancements in software and consumer drone technology, SfM and drones have emerged as an excellent platform for rapidly generating accurate and high resolution point clouds and digital surface/elevation models, at a lower cost than comparable technologies like lidar or terrestrial laser scanning. In a sandy beach evironement, this can be especially useful as waves, tides, and especially large storms constantly move sand around. However, drones do have some limitations, mainly due to governement regulations and weather, which can totally restrict flight. For example, FAA regulation prohibits flight over crowded areas, making UAV-based surveys impossible on popular beaches without totally restricting access to the beach. To work around flight restrictions, a camera can be mounted on a tall pole to gain a similar aerial perspective, and promises to be a viable solution to the limitations of UAV-SFM. The goal of this study is to compare and evaluate both UAV and pole-baed SfM for routine monitoring of beach erosion.

Field surveys

Three monthly surveys were conducted with both systems in September, October, and November 2020. The UAV system consisted of a DJI Mavic 2 Pro, operated using the PIX4Dcapture app for Android, while the pole system was a GoPro Hero 8 on top of a ~4 m teloscoping pole, with the camera mounted at a downward-facing angle. A 200x100 m stretch of beach on capers island, SC (pictured below) was used as the study area.

Planning flights with the PIX4D capture app is very straigtforward. All you need to do is drag a rectangle or polygon that covers the study area, and define relevant flight parameters like height, camera angle, grid pattern and flight speed. The drone can cover an area of this size quite quickly (our longest flight was about 20 minutes, and shortest around 7), so for each survey we flew five drone flights for each survey campaign.

Beacuse the pole photogrammetry system is just carried by hand, it moves at a much slower speed. The lower camera altitude also means that far more images are required to cover a given area. All this means that a complete survey is far more time consuming, about 90 minutes compared to potentially under 10 minutes for the faster drone flights. preliminary tests showed that spacing trasects by 4.5 m would yield sufficient overlap between images, meaning that a complete survey would take aout 20 transects parallel to the beach. If you unravel the complete survey into a straight line, this means about 4 km of walking to survey a 200 m long stretch of beach.

SfM processing was all done using Pix4D. In general, the UAV surveys came together very easily, for the most part only needing georeferencing using ground control points we collectd with an RTK-GPS. We did run into some issues of doming (see James & Robson, 2014), but this was relatively minor and fixed by adding GCPs. However, pole photogrammetry results were much more difficult.

Pole photogrammetry Pix4D struggles

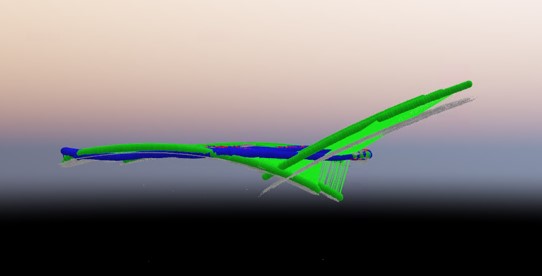

Inital results showed severe doming, shown below, rendering resulting point clouds/DSMs completely unusable. James and Robson (linked above) indicate that the main cause of doming is innaccurate camera calibration, failing to properly account for distortion characteristics. Now Pix4D contains a database of common camera models, including the GoPro Hero8. These are usually quite accurate. However, we noticed that the later GoPro models are all listed as perspective lenses, while they are in reality fisheye lenses. Using this default camera model results in a severely domed and borken reconstruction.

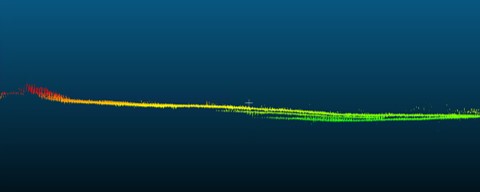

However, earlier GoPro cameras have a correct camera model and appear to use identical lens and sensor hardware as the Hero 8, meaning that the relevant camera charaacteristics can be repleaced with those form an earlier camera. This greatly improved results, with reconstuctions finally recognizeable as a beach surface. There still remained many areas that were broken, likely due to insufficient overlap, inability to find matching features in the beach surface, or a combination of the two. Adding ground control points and manual tie points helps somewhat, but does not totally alleviate problems. In fact, adding too many MTPs (>~80) can cause further issues. Unfotunately, it was not possible to totally rectify pole photogrammetry-derived products, making them unusable for erosion analysis. The dominant error is what we call ghosting, where an area is reconstructed as multiple vertically offset layers, making it impossible to identify which represents the true surface. These ghosting erros can be seen in the DSM cross-section below.

Change analysis

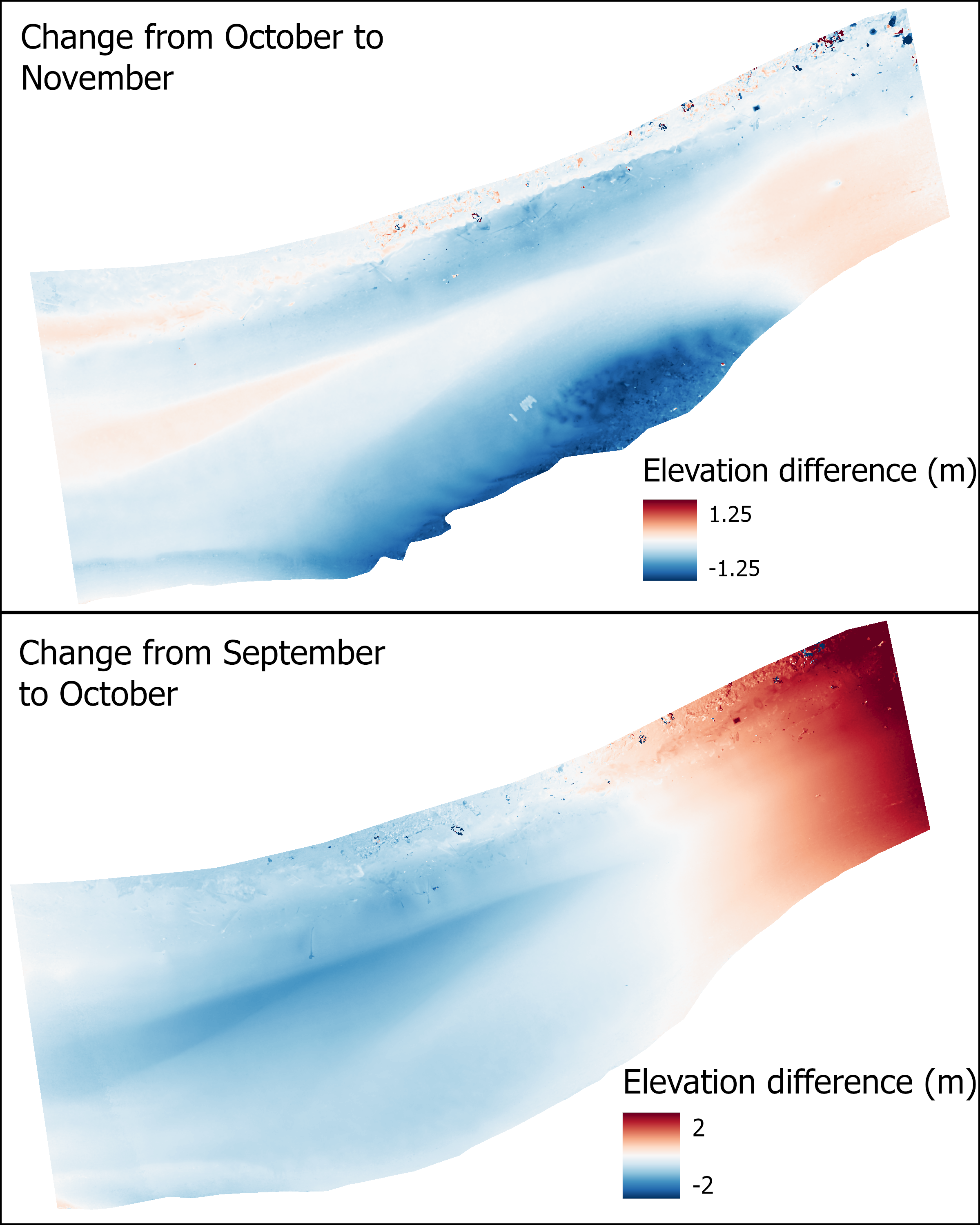

Elevation change analysis was done using the DEM of Difference (DoD) method, where one DEM (or DSM in this case–these are interchangeable on a barren beach) is subtracted from another, yielding the difference in elevation. Although the pole photogrammetry products were not usable, the UAV produced excellent DSMs which can be effectively comparesd to one another, or to lidar-derived elevation data. The September UAV survey was the only DSM with any issues, presumanely due to a camera calibration or GCP correction issue. As shown below, the DoDs indicate significant changes in beach volume and shape over the month long interval between flights.

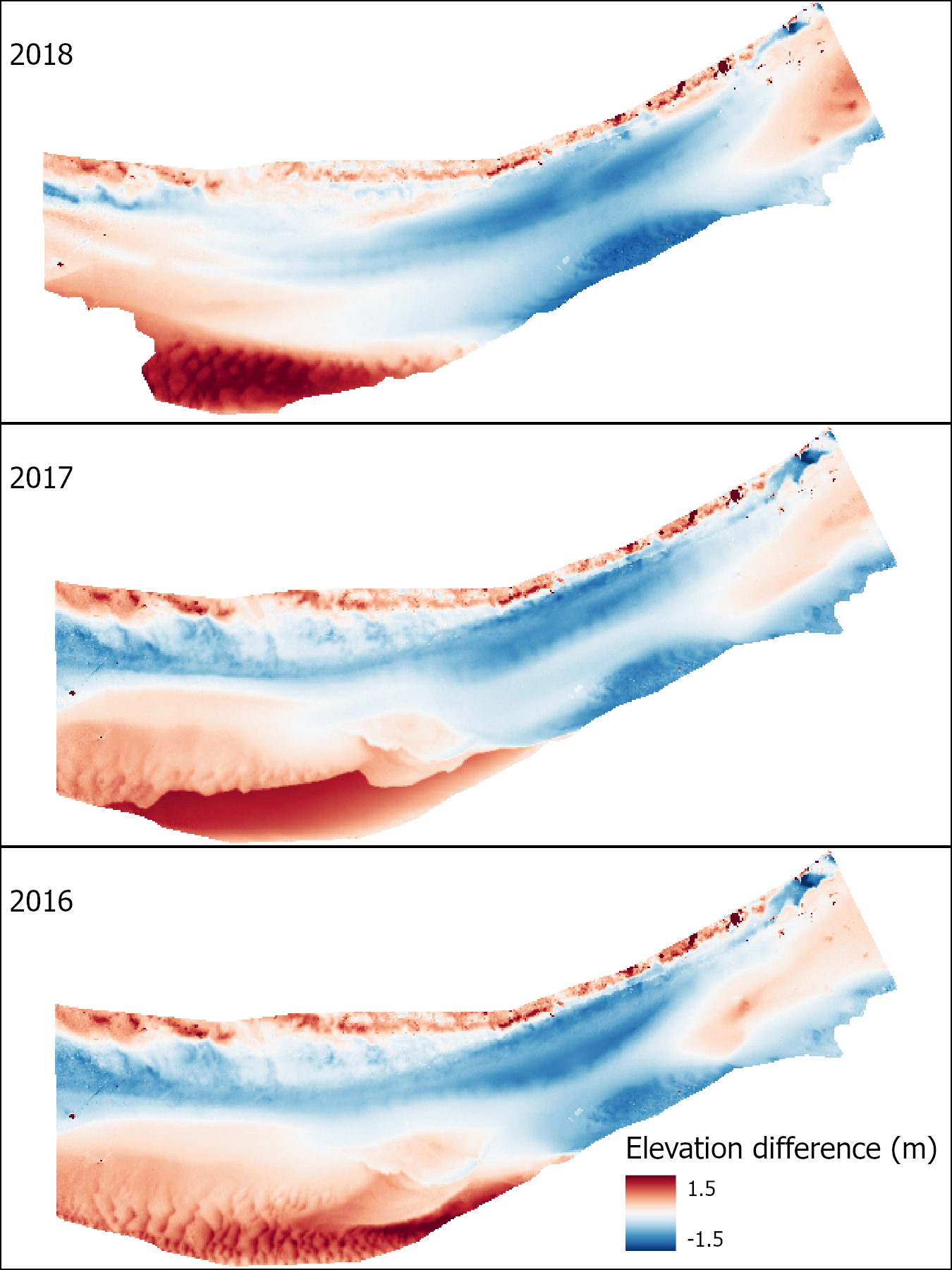

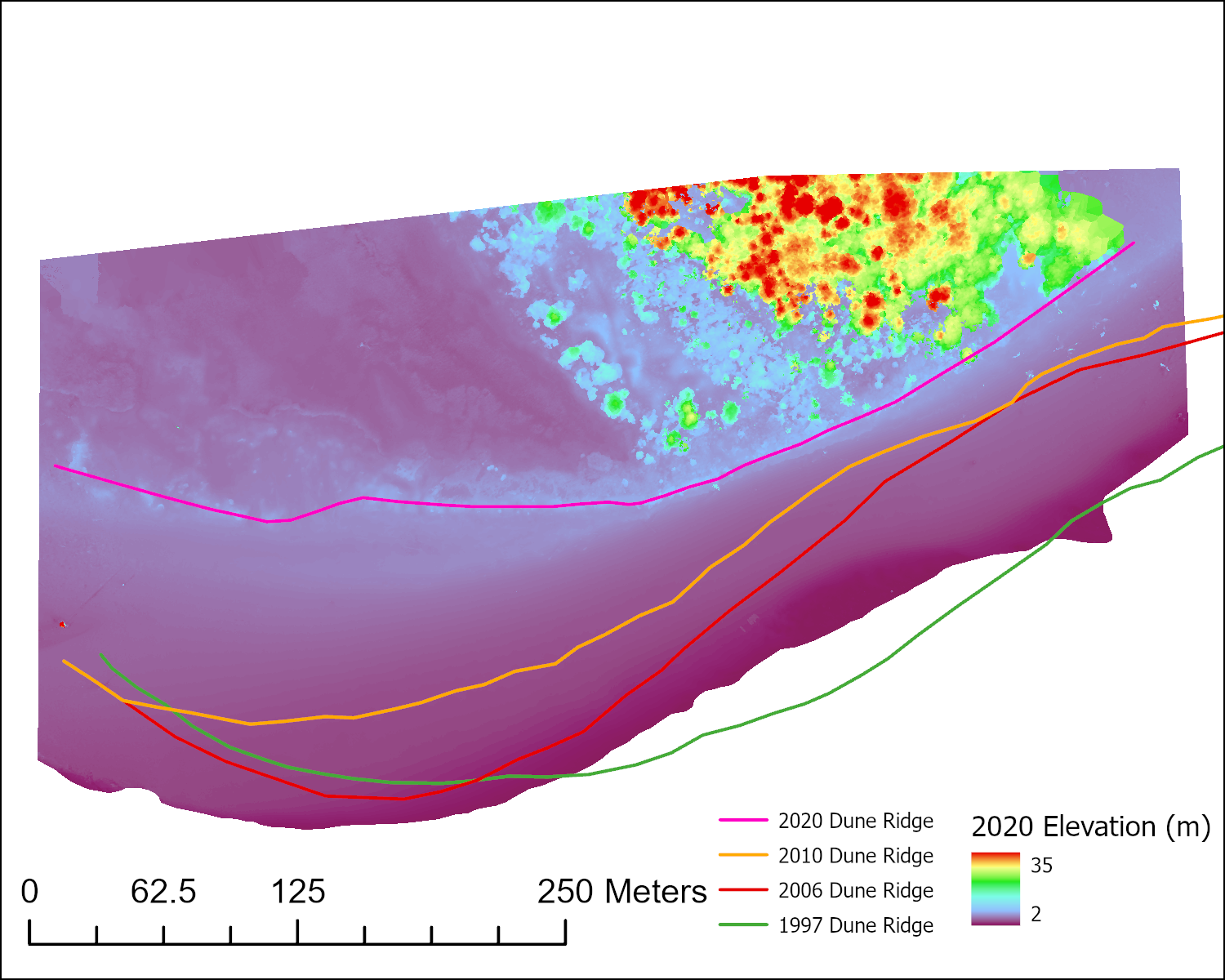

Comparisons of the November UAV survey to older lidar flights show siginificant long term change.

Older lidara datasets (i.e. from 2010 and earlier) aren’t as useful for direct elevation change, as the present beach was covered by trees. However, shoreline change can be estimated by tracking the position of the foredune ridge. This is used rather than the actual shoreline, as the shoreline is highly variable with the tides, and dependant on the water level when each flight was flown.

Conclusions

Comparing the UAV and pole photogrammetry platforms, it is clear that UAVs are the superor choice in every respect. Althouh limited by certain flight restrictions and more expensive, pole photogrammetry is a very slow, labor-intensive process, and needs major imporvement to produce any useable results. The NEIL Lab is currently working on improving pole photogrammetry to find a solution to problems encountered here. Some possible improvements to the pole photogrammetry system used here include adding an RTK-GPS to the camera, as the GoPro’s onboard GPS has extremely poor accuracy. Accurate geolocation, especially if paired with camera roll, pitch, and yaw can both accelerate and improve photogrammetric processing. Another would be to narrow the gap between adjacent transects, to increase overlap in images. Although tests showed that the ~4.5 m spacing used in these surveys would be sufficient, it evidently could be better. The third improvement would be to mount the pole and camera system to an autonomous ground rover, to automate the surveying process, similar to a drone flying a pre-planned flight. This would aslo ensure consistent transect spacing, while significantly lowering the workload required to execute a survey.